Afghan Chronicles

Directed by Dominic Morissette. 2007. 52 minutes. In Dari and Pashto with English subtitles.

Study Areas: Afghanistan, Social Change, Democracy, Media.

Photo Copyright 2007 Dominic Morissette.

Photo Copyright 2007 Dominic Morissette.

This insightful and thought-provoking film was shot mainly in 2006 when the Canadian filmmaker Dominic Morissette spent time in Kabul documenting the activities of people associated with the Killid Media Group that was then composed primarily of two magazines and one radio station. One of the magazines, Mursal, specifically caters to women, and a large part of the film deals with women’s issues not only insofar as the magazine is concerned, but also in the context of Kabul’s urban culture, unique in preponderantly rural Afghanistan. The film briefly mentions a few locations outside Kabul, and these cursory references collectively emphasize the city’s problematic relationship to the remainder of the country, particularly the eastern Ghilzai tribal territories to the east and southeast of Kabul and the city of Qandahar in the south of the country. One important point educators should note when using this film in class is to not fall into the analytical trap of equating the country of Afghanistan with the city of Kabul.

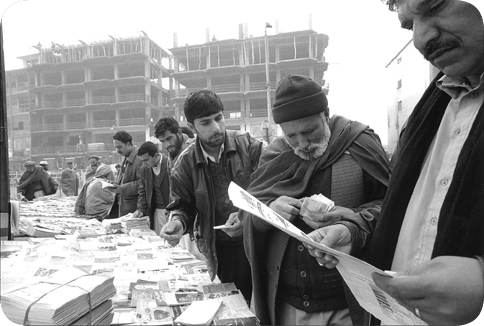

The film is both a documentary and an ethnography, and while it is most suitable for university settings, it is also accessible to well-prepared junior college and high school students. It provides engaging cinematography of Kabul and an absorbing series of first-person narratives. The people at the center of the film are tracked as they go about their daily work for the Killid Media Group (KMG), but two individuals not directly connected to Killid are also interviewed. Three main figures at the KMG receive the bulk of the attention in the film. The first is Kamal Nassir, whose job is to deliver large bundles of Killid and Mursal magazines to retail vendors in and around Kabul. Through the windows of Kamal’s delivery van, viewers see the streets of Kabul, and the film also follows Kamal on foot as he delivers bundles of magazines to various stalls and shop around the city.

Viewers are fortunate to experience the oratory of one of Kamal’s customers, a street vendor who expresses distaste for the highly sexualized Indian and foreign pictures found in the KMG publications. Speaking in Pashto, the vendor details a much larger concern for the cultural consequences represented by the pictures that he views as inextricably linked to the warped and contrived versions of democracy and freedom forcefully installed in Kabul and other locations in Afghanistan. This interview is significant for giving voice to what can be glossed as advocacy for the maintenance of values associated with local and so-called traditional elements of Afghan culture involving speech, clothing, and the presentation of self in public life.

A second important feature of this interview, while not explicitly noted by the filmmaker, is in fact central to understanding cultural dynamics in and beyond Kabul. The key issues for students to be aware of are both the ordinariness and complexity of interaction between languages in Afghanistan. The highly illuminating dynamic between spoken Dari or the Afghan dialect of Persian (as opposed to Iranian Farsi) and various dialects of spoken Pashto is not captured by the subtitles that unfortunately do not indicate original languages. Through Kamal, viewers are introduced to an unemployed nurse vending candy and trinkets from a pushcart in front of a school to make ends meet for his large family. We also encounter the keen-eyed social commentator Abdul Ghaffar who has been operating an old wooden box camera on the streets of Kabul for over 50 years. The film gives Ghaffar an opportunity to share his folk-philosophical views about current and recent historical conditions in Kabul. This experienced, articulate and street-wise voice echoes the many hardships faced by Afghans for well over a full generation, notably that of perpetual hunger.

Kamal was a refugee in Iran before returning to Kabul to work for KMG after 9/11 and the subsequent international ouster of the Taliban from power in Afghanistan. The second main character in the film, Farooq Wurukzai, also experienced life as a refugee, but he spent time in Pakistan (as did the majority of Afghan refugees) before returning to work as a main anchor for the KMG radio station. His story will help educators address the broader point of the role of returning refugees, exiles, and members of the Afghan diaspora. Viewers see how Farooq handles calls from the public and expounds on current issues including government corruption and violence against women. When on the air, Farooq speaks in Dari and invokes Persian poetry and metaphors in his social and political commentaries, but it is important to note the film repeatedly shows an anonymous female co-anchor who speaks much more concisely and directly in Pashto when broadcasting.

The main character of the film is Marzia Monsif, a Dari-speaking journalist who appears to have been born and raised entirely in Kabul. Through Marzia and her colleagues Hafiza Rahim and Nargis Hashimi, viewers learn about Mursal and the contentiousness and sensitivity posed by some of the content of this women’s magazine for Afghan society. Although Mursal publishes apparently less controversial items such as recipes, even they require editorial discussion about whether they are local or foreign, as that basic distinction can attract or alienate potential readers. This ground-level reality allows viewers to see why even more deeply culturally encoded issues like hairstyle, makeup, and fashion can be more easily perceived as corrupting intrusions, meriting heightened editorial discussion.

Mursal engages issues related to maternal healthcare and family planning. These involve domestic affairs and thus carry the potential for stigmatization and dishonor for the males and females of the household in many different ways. Mursal’s activism and advocacy are also directed at the central institution of marriage in Afghanistan. The film records the production of a scene staged to generate photographs for a story on male impotency, and it also offers footage of a doctor’s office where patients are advised not to marry relatives. The film briefly trails Marzia as she travels around Kabul to pursue her work on these women’s issues that also have significant effect on men, but her presence in the film is primarily indoors.

The filmmaker made two visits to Kabul, and on the shorter second visit he found Marzia at home unemployed after having left her job at Mursal due to unspecified personal and familial pressures connected to her work at the magazine. It is made clear that intimidation and threats left Marzia too terrified to work at Mursal, and the film concludes with her regrets about the return of the Taliban to power. To fully contextualize Marzia’s plight, it will be important for viewers to situate the release of this film in 2007 with the major anti-Taliban offensive conducted by international occupation forces in the Helmand province in 2008.

In addition to its twinned themes of gender and media, the film uses war to contextualize its subject matter. The film provides viewers with a very clear sense of how the war-driven economy of Kabul created rampant inflation and severe economic displacement and disparities for a population that swelled from approximately 300,000 to 3,000,000 between 1979 and 2007. The constant coughing in the audio background of many scenes raises important questions about the overall state of public health in Kabul. A passing reference to the increasing frequency of birth defects in the doctor’s office deserves classroom notice. This dire phenomenon can be explained by the occupation forces’ use of depleted uranium in munitions; it has entered the already fragile water supply system of the country.

Arising from these three primary themes are two embedded issues that can be productively extracted to fuel class discussion. The first is the power of images and pictures in a social environment where literacy is low. To enhance student understanding of the critique offered by the Pashto-speaking vendor, students can be prompted to consider how and why images of Afghanistan have come to carry such weight, including arguably the world’s most famous photograph of ‘the Afghan girl’ that appeared on the cover of a National Geographic Magazine in 1985 at the height of the Soviet Union’s presence in Afghanistan, and those of a similarly unveiled Queen Soraya that are widely believed to have contributed to the forced abdication of the modernizing Afghan King Amanullah in the 1920s. Secondly, students should be prompted to consider how and why images, information, and “data” emanating from Kabul come to represent the country as a whole. The issues raised by such an interrogation concern inter-urban and urban-rural relations, consideration of which help to demystify Afghanistan while adding further comparative value to the film.

Afghan Chronicles merits wide classroom circulation. It is highly recommended for globalists and regional specialists who cover modern Central Asia, South Asia and/or the Middle East in their classrooms, as well as for gender-focused courses and any offerings that include space for contemporary women’s issues.

Shah Mahmoud Hanifi is an Associate professor of History at James Madison University.

Afghan Chronicles is available for purchase or web streaming on the National Film Board of Canada website.

Last updated December 11, 2014.